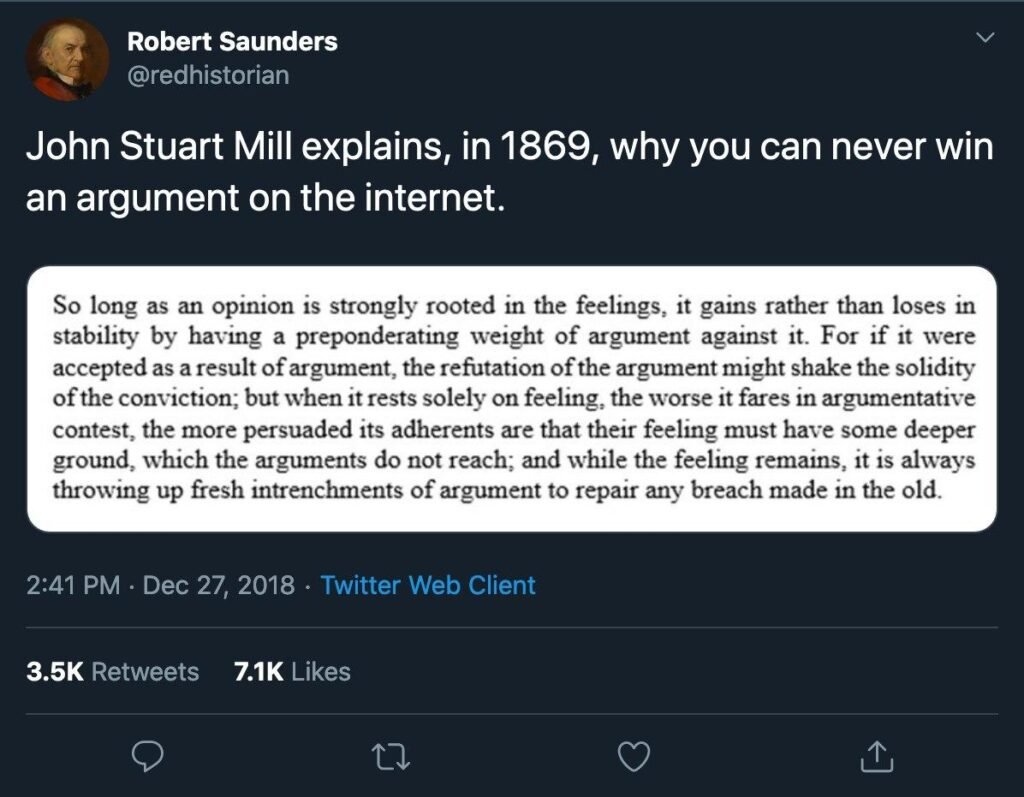

Inevitable characteristics of social media are wildly misleading facts and spurious arguments. However, no matter how infuriatingly wrong anyone is, or about how much counter-evidence you have at your hands, starting debates on the internet hardly lets people change their minds. About a century-and-a-half ago, the British philosopher John Stuart Mill explained, in a few simple words, why those arguments can probably not go anywhere. Mill’s concept neatly relates to heated and pointless internet disputes, as historian Robert Saunders says.

IS IT ALL ABOUT THE TRUTH?

Mill illustrates the often-ignored truth that many perspectives are not based at all on truth but on emotions. And thus, conflicting fact points do not change emotionally ingrained arguments, but only trigger individuals to reach deeper into their sentiments to hang on to those opinions.

Intuitively, most persons realise that feelings inspire opinions, and function accordingly. To better persuade others of our views, we use rhetorical tactics, such as verbal flourishes and confident mannerisms. And we know that furious objections to, for instance, evidence showing that same-sex couples’ children fare just as heterosexual parents do, are based on emotional bias rather than a deep-seated seek for the truth.

EMOTIONS HELP IN MAKING CHOICES

These instincts regarding the value of emotions are validated by some studies. For instance, people who have a brain injury in the region responsible for processing feelings often struggle to make choices, contributing to the significance of emotions in choosing between two paths. And chartered psychologist Rob Yeung, whose book How to Stand Out explores the strength of feelings rather than reasoning, by encouraging others to agree with you, leads to studies demonstrating that the use of metaphors motivates people to make choices.

Online, it is easy to lose track of such emotional instincts because we can’t see the faces of people or their moods. There may be a temptation to bombard people with contrary beliefs with “facts,” instead of communicating with and acknowledging the feelings of other people. But even seemingly strong points of facts, such as the periodic table, are often based on subjective perspectives; a broad metaphysical philosophy called “social constructivism” claims that facts are always a representation of ideals that are socially formed. There are also many ways to interpret a single area of information and so, while certain people would want to believe they’re right about something, there are surprisingly few conflicts of an unambiguously accurate opinion.

CONCLUSION OF INTERNET DISPUTES

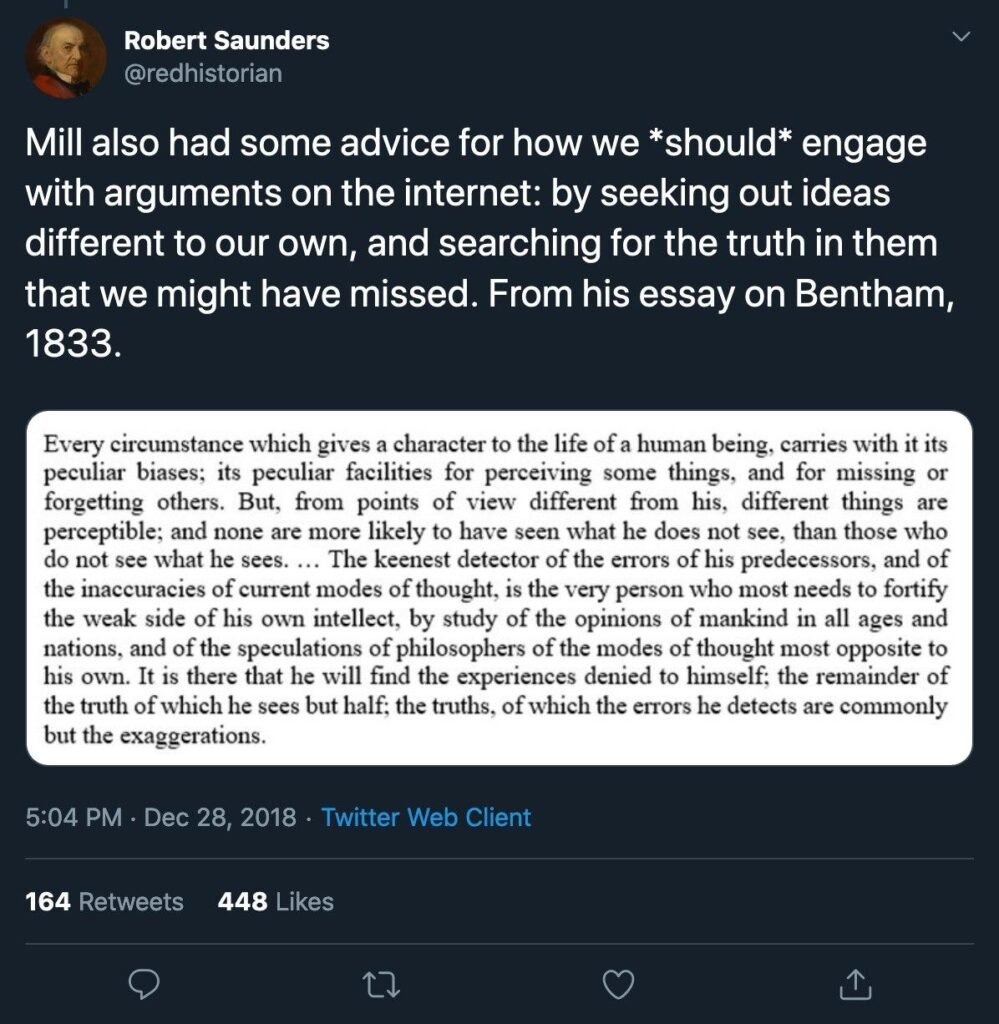

Maybe there is no chance of encouraging others to change their minds on the internet. But Mill does point to a different approach, as Saunders notes.

We should be open to changing our own minds instead of having to convince others and look for evidence that opposes our own steadfast perspective. Perhaps it would turn out that those who argue with you just have a solid view of the truth. There is a small possibility that you’re the mistaken one, after all.